loading...

It’s no surprise to the people who know me that I’m obsessed with the Bon Appétit Editor’s Letters—

I love the sweet, quick titles, sudden paragraph breaks, and the ways images meet text within 8 x 11 pages.

[In truth – I could never be one of those technology erudites quick to dismiss the glossy periodical. I love the way it looks and feels, like an old-world traditionalist. Hand me my newspaper stand, and I’ll keep reading.]

I even love Adam Rapoport’s strange ability to cover so much ground in so little space (I call this “strange” because I have yet to compose a perfect 250-word article).

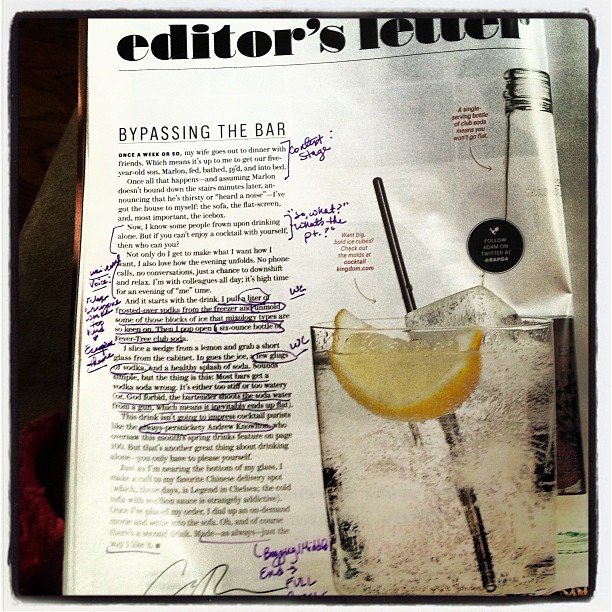

In fact, my copies of Bon Appétit often have a “sticky-page” quality where issues fold open to the “good stuff”—often a recipe or two, but always the Editor’s Letters. Sometimes, I start reading, get to Adam’s letters, and, then, don’t move forward at all. Instead, I read them again and again, hovering over phrases and words, circling word choice and diagraming sentence structure.

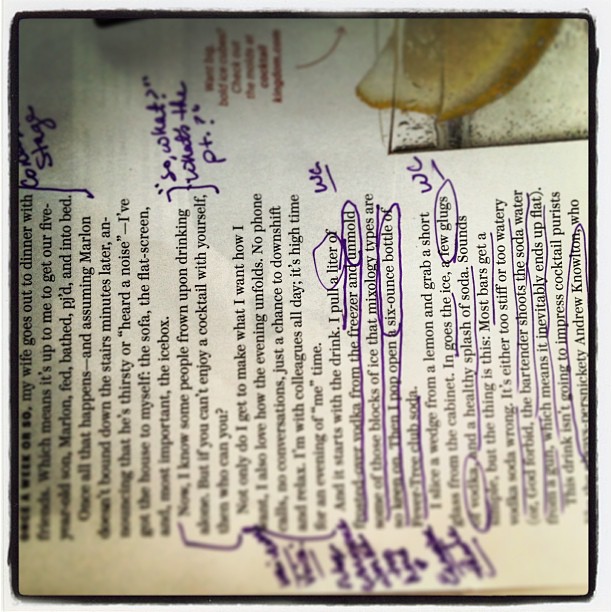

I once had a high school English teacher tell me that if you were to take a piece of writing and flip it horizontally (that is, on its side), you could see the rhythm of a writer’s prose as it ascends and declines.

It’s a fascinating image, really, and one I’ve never forgotten:

Pictured: Rapoport’s April (2013) letter with stiff, thick starting points and jumpy, casual peaks in the center right before it balances out to the rhythm which opens it. Short Editor’s Letters make for great examples of how good food writing should run like everyday speech, or possess a certain “back and forth” quality to its prose.

As a writing teacher, columnist, blogger, and cookbook author, there’s a certain taken-for-grantedness in these short openings to glossy periodicals. I think most readers skip this page (although, I can hardly understand why), but it’s one of my favorite contributions in the whole mag. Like little episodes on “how to write” or “how to think about food” or “how to balance personal details with recipes,” the editor’s letter evokes crafted (yet casual) journalism of which I can’t get enough.

Plus, reading good food writing has its perks: it helps us to create our own good food writings.

As I was marking up the last letter, I thought I’d share my marginalia and notes on what makes these pages worth savoring, and what makes them particularly “bon appétit.”

Editing the Editor: Writing Tips & Tricks from Adam Rapoport (April 2013):

Pictured: circled word choice and teaching notes.

1 – Context & Stage:

“Once a week or so, my wife, goes out to dinner with friends. Which means it’s up to me to get our five-year-old son, Marlon, fed, bathed, pj’d, and into bed.”

– Here, Rapoport explains not only how he’ll go from pajamas to seltzer, but also how this happens in a sweeping moment (or sentence).

With one sentence, Rapoport packs –

(1) the setting, or adverbial phrase: “Once a week or so,”

(2) parallel structure: “fed, bathed, pj’d”

(3) nuanced and creative word choice: “pj’d”

(4) identifiable imagery: we’re all familiar with the image of the tired, busy parent trying to put down a child. It’s easy to grasp and quick to follow.

2 – Vivid Detail & Interjection

“Once all that happens—and assuming Marlon doesn’t bound down the stairs minutes later, announcing that he’s thirsty or ‘heard a noise’—I’ve got the house to myself: the sofa, the flat-screen, and, most importantly, the icebox.”

The “hero’s” journey is not quite done: here, we see that life happens and little things can get in the way as we attempt to relax at the end of the day. (All the more reason why we’ll be discussing seltzer and ice boxes.)

Worth noting:

(1) strong word choice – the child doesn’t “come down the stairs,” but rather, “bound[s] down the stairs”; additionally, the child’s reasoning—”heard a noise” or “thirst” instantly explains why he’s there. Nothing is left blank in this sentence. All the who, what, when, where questions are perfectly in place.

(2) paints a picture: what Rapoport savors in his alone time is instantly visible: “the sofa, the flat-screen, and, most importantly, the icebox.” We know exactly what beckons him at the end of the long day, and we’re (probably) a little bit jealous.

(3) more on word choice: Rapoport doesn’t say, “a bottle of scotch” or “the bar,” but he’s far more specific–“the icebox,” an image or word that may not initially occur to us as we craft our posts. If I were writing about an end-of-the-day cocktail, I’m pretty sure I’d jump straight into the wine. The fact that Rapoport shifts the focus (unexpectedly) onto big chunks of ice indicates a strong sense of what can be romanticized in food writing: everything. Everything from the perfect tumbler to the perfect block of ice.

3 – “So, what?” or “What’s the point?”

“Now, I know some people frown upon drinking alone. But if you can’t enjoy a cocktail with yourself, then who can you?”

As the third paragraph to his letter, Rapoport gets straight to the point: hey, those of you reading this who think “drinking alone” is for the indulgent-Don-Draper types need to understand why this letter exists—learning how to make a cocktail for yourself is about as important as learning to do anything else in the kitchen or at the bar.

Here’s why:

(1) addresses the reader: Rapoport isn’t just talking about himself, he’s talking about the reader’s (assumed) misgivings as well as his own ability to bypass solitary Don Draper cocktails. There’s a lesson here in mixology which is remarkably simple: learning how to prepare drinks based on your own preferences. Then, you might learn something about preparing drinks for others too.

(2) answers the question, “So, what?” or “What’s the Point?”: as mentioned in the previous paragraph, the point is simple: to learn how to mix properly in an unexpected and private way. And, to learn what it is that you like about drinking.

4 – Relax, Relax, Relax

“Not only do I get to make what I want how I want, I also love how the evening unfolds. No phone calls, no conversations, just a chance to downshift and relax. I’m with colleagues all day; it’s high time for an evening of ‘me’ time.”

Perhaps one of the most common tropes in food writing is nostalgia. I read too many recipes (sometimes even my own) in which we connect our senses with time and place. (Thanks, Proust.)

Here, Rapoport shifts away from nostalgia into a similar emotion we can all understand: instead of savoring the past, we savor the moment, recognizing just how special it is to unplug and unwind.

Here’s how:

(1) strong word choice: “downshift” and “relax” overtake common words we might use like, “get comfortable” while more common phrases like “me time” connect Rapoport with the reader (we all want “me time” at some point in the day).

(2) universal theme: everyone knows the stress of a long and busy day, and I imagine readers of Bon Appétit are especially prone to this message since food can be one of the best gateways for escaping stress whether you’re cooking your favorite meal, eating with friends, or, yes, making a cocktail.

5 – Recipe is in the Details

“I pull a liter of frosted-over vodka from the freezer and unmold some of those blocks of ice that mixology types are so keen on. Then I pop open a six-ounce bottle of Fever-Tree club soda . . . In goes the ice, a few glugs of vodka, and a healthy splash of soda. Sounds simple, but the thing is this: Most bars get a vodka soda wrong. It’s either too stiff or too watery (or, God forbid, the bartender shoots the soda water from a gun, which means it inevitably ends up flat).”

Instead of writing the “recipe” for his favorite seltzer and vodka cocktail over ice, Rapoport narrates the recipe as a story, telling us all the highlights:

(1) ingredients: you might not notice it (and I didn’t upon first read), but Rapoport endorses a specific soda water brand (“Fever-Tree club soda” which retails for (essentially) $6.90 a bottle or $27.98 / 4-pack at Walmart; also – it’s possible he gets the size of the bottle wrong. Citing “6-ounces” when bottles appear to be sold in 6.8-ounces here. I’m assuming 6-ounces is stylistic because it “sounds better,” but it’s erroneous nonetheless).

Rapoport tells you how much (exactly six-ounces) and the order of ingredients (ice, vodka, then soda water, or the “ingredients list”). Just like those early Victorian recipes in which ingredients were embedded in the methodology, this recipe appears like a throwback to simpler times where ingredients evolved as readers worked their way through a recipe.

(2) simple: three ingredients and method makeup one sentence.

(3) word choice: again, Rapoport’s word choice stands out as a prime example of clear, specific, and certain food writing. He doesn’t measure the vodka, but eyeballs the ingredient based on “glugs,” indicating this recipe is written as much for him as it is for you, the reader.

(4) critical context: how this recipe can be done “wrong” and the common pitfalls. I think most people think of a “vodka soda” as the kind they’d order at their neighborhood bar, but “shoot[ing] the soda water from a gun” suddenly takes on a new light – we’re appalled by the dangerous imagery of haphazard bubbly water destroying your perfect drink.

6 – Full Circle

“Just as I’m nearing the bottom of my glass, I make a call to my favorite Chinese delivery spot (which, these days, is Legend in Chelsea; the cold tofu with scallion sauce is strangely addictive). Once I’ve placed my order, I dial up an on-demand movie and settle into the sofa. Oh, and of course there’s a second drink. Made – as always – just the way I like it.”***

Like all good food writings, Rapoport comes “full circle” with a clear beginning, middle, and end. In these last words he reminds us why the drink was made in the first place (time to “settle into the sofa” and “wind down”). Better yet, there’s an overarching theme –

Drinks made just the way you like it.

– Helana

***Note: there are criticisms here that should be noted: the image of the nuclear family gives me pause (not every family functions this smoothly). Additionally, the image of dad reclining on the sofa is a highly gendered one. If the editor to Bon Appétit were female, I can’t help but wonder if this letter would unfold similarly? When the child is down, is it “wine time” with a romantic comedy and nail polish? OR, is she expected to unload the dishwasher, start a load of laundry and reply to company e-mails? I choose not to engage this gender inequality here, but simply point out that Rapoport’s letter is informed by a male perspective.

—

Follow me on Pinterest: http://pinterest.com/helana/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/DancesWLobsters

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Clearly-Delicious/103136413059101

Tumblr: http://clearlydelicious.tumblr.com/

Instagram: http://instagram.com/helanabrigman

Editing the Editor: Writing Tips & Tricks from Adam Rapoport (April 2013),

No Comments